The algorithm knows

Lessons from a Y2K dot-com

Sitting at a desk in a high-rise on East 43rd Street, we were a group selected from different fields: editors, writers like me, marketing personnel, sales, and programmers. We were part of the newest dot-com wunderkind, Yack.com.

I had taken leave of the paper I’d edited for the past three years to join Yack, which dangled a salary double the one I was making plus “stock options.”

We sat at our Dilbert-like cubicles trying to figure out what we were trying to do: capture the ether, bits and bytes at a time, and somehow coalesce all this into a usable, monetizable format.

The idea was a TV Guide for the internet, with all the streaming, live, and on-demand events available by category with reviews and recommendations. I was a “content aggregator.” Yack.com used human editors to ensure that live streams were actually “live” and functional — a major hurdle in 2001.

While we used early “spidering” programs like WebCrawler and DeepSeek to map the growing web by downloading and indexing text and images, we knew that technology alone wasn’t enough.

For the internet to truly compete with television, it required human curation. Without human-led navigation tools like Yack.com, the promise of live internet streaming would be lost in a sea of broken links and unsearchable video. We aimed to provide a “structured experience” for an unstructured medium — a vision that eventually paved the way for modern streaming interfaces.

Our most successful product was a hard-copy magazine with event listings, including those of independent production companies like Burly Bear, the College Television Network, and Heavy.com.

The problem is, 90% of the audience would be unable to watch these programs.

To understand the obstacles is to understand the “codec wars.” A codec — a mashup of the words “coder” and “decoder” — is the formula used to compress data. In 2000, there was no universal standard; it was a digital Tower of Babel. If a webcast was encoded for RealPlayer, a user with Microsoft Windows Media was effectively locked out. They would click a link only to be met with a prompt to download a 10MB installer — a death sentence on a 56k modem.

The company burned through $35 million faster than an oligarch in a yacht showroom. All of us were out of work within a year; today, traces of the company can only be found on the internet’s “Wayback Machine.” Some people walked away with “golden parachutes.” I went back to interviewing people with a tape recorder and a reporter’s notebook.

Unmapped Territory

Marshall McLuhan wrote in Understanding Media that art is “advance knowledge of how to cope with the psychic and social consequences of the next technology.” In the modern era, that next technology is the algorithm.

Before the era of centralized search, we relied on programming techniques known as “spidering” to populate the website — automated, many-limbed programs that could pluck past web addresses to find the “deep links” of content. Even before the advent of Google, search engines like AltaVista, Yahoo, and MSN vied for clicks. Many were at the heart of the dot-com boom; some survived, most didn’t.

These engines provided users an opportunity to search without human gatekeepers. Using a simple search box, a user could find something they were more or less looking for, though the experience was often clumsy. Since few people had the high-speed technology to play movies and games, we were mostly taken to “static” pages that provided all the pleasures of reading … a book.

By the time Google arrived, technology and broadband had caught up. The product that wasn’t available for Yack in 2001 came online with YouTube in 2005; Hulu and Netflix followed, and in the 2010s, we were able to “cut the cord.” Today, speed is not an issue — broadband is ubiquitous even in the most remote regions.

Words Matter

In the two decades since, the intent of Yack.com — with its human annotators and editors — has been completely consumed by “the algorithm.”

Google refined the “spidering” theory into a highly sophisticated process of crawling, indexing, and ranking. Their modern Googlebot discovers billions of pages and analyzes them in a massive index. Power has shifted from human navigation to recommendation algorithms. When you search, algorithms weigh hundreds of factors to serve a result in a fraction of a second. In other words, an uncountable number of virtual “Yack employees” are now in the service of big tech to guide us where they want us to go.

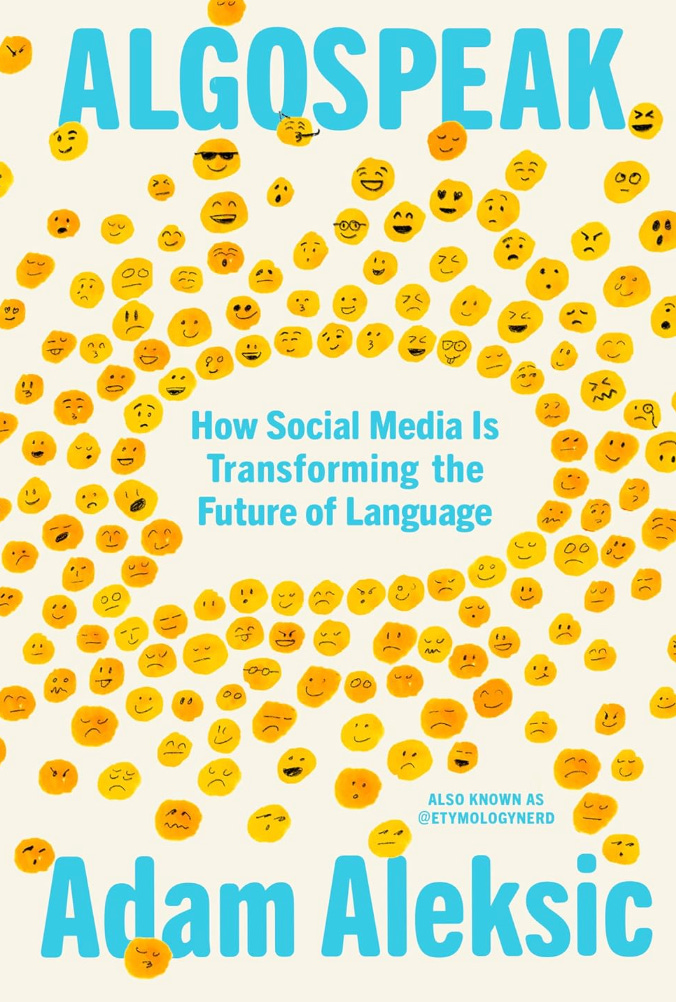

Adam Aleksic writes in his new book Algospeak: “The massive success of the personalized recognition algorithm relies on a few tricks, but the underlying principle is quite intuitive. If you like a certain kind of content, you’ll probably like the other content similar to it.”

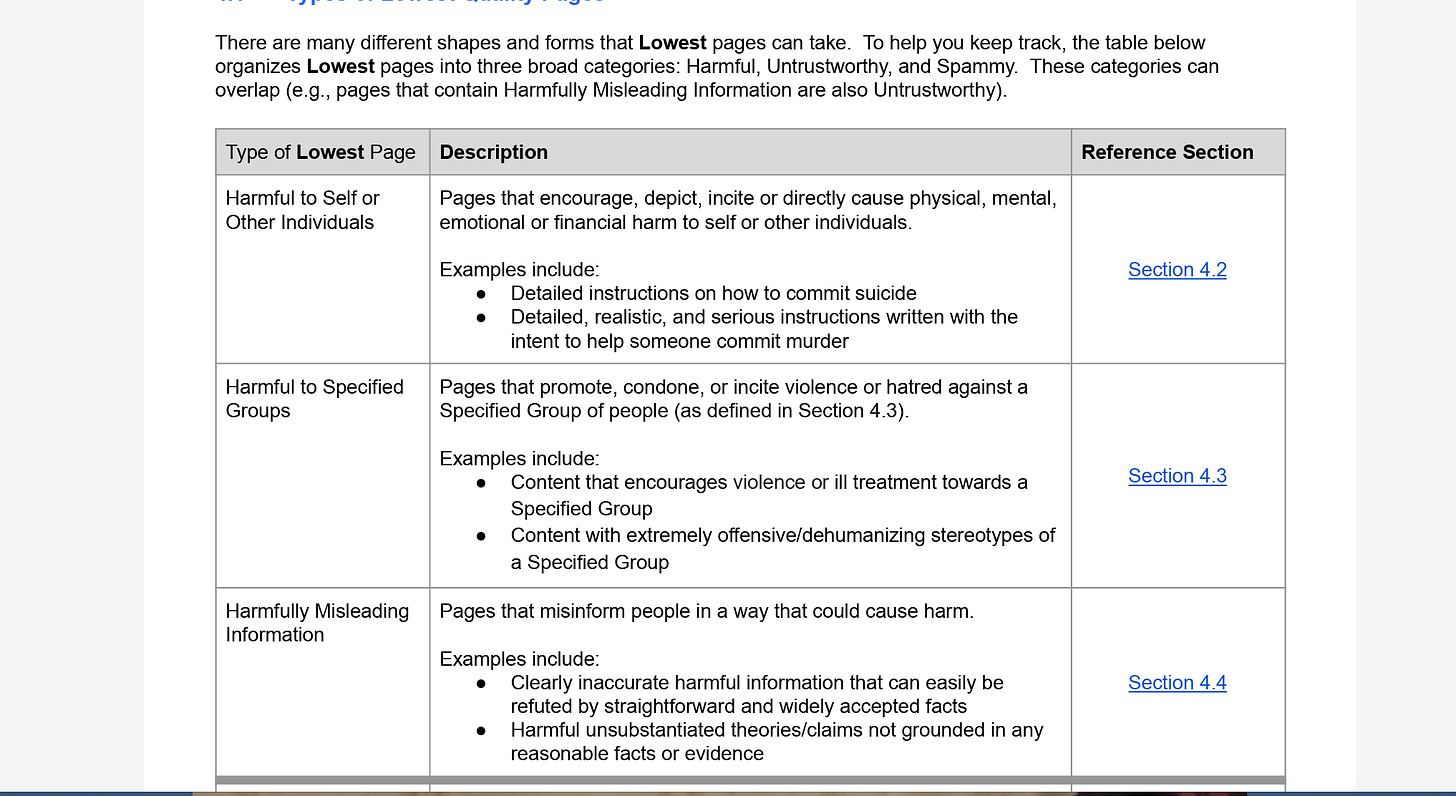

Unlike the human editors of 2000, modern algorithms don’t pick and choose based on their own or the viewers’ interest. They track engagement signals to determine “relevance.” According to Google’s Search Quality Rater Guidelines — a 182-page handbook provided to its evaluation teams — search results should help people.

“Search results should provide authoritative and trustworthy information, not lead people astray with misleading content,” the guidelines state. “Search results should allow people to find what they’re looking for, not surprise people with unpleasant, upsetting, offensive, or disturbing content. Harmful, hateful, violent, or sexually explicit search results are only appropriate if the person phrased their search in a way that makes it clear that they are looking for this type of content.”

In the 2020 horror movie Host, participants in a Zoom meeting inadvertently summon a spirit that terrorizes them all. Today, the algorithm is the medium through which we summon our own digital spirits.

Adam Aleksic writes:

They don’t recommend content for you; they recommend content based on others similar to you. Nor do you make your own decisions. Your decisions are now curated for you under the guise of personalization, while in reality they’re engineered to make platforms as much money as possible.

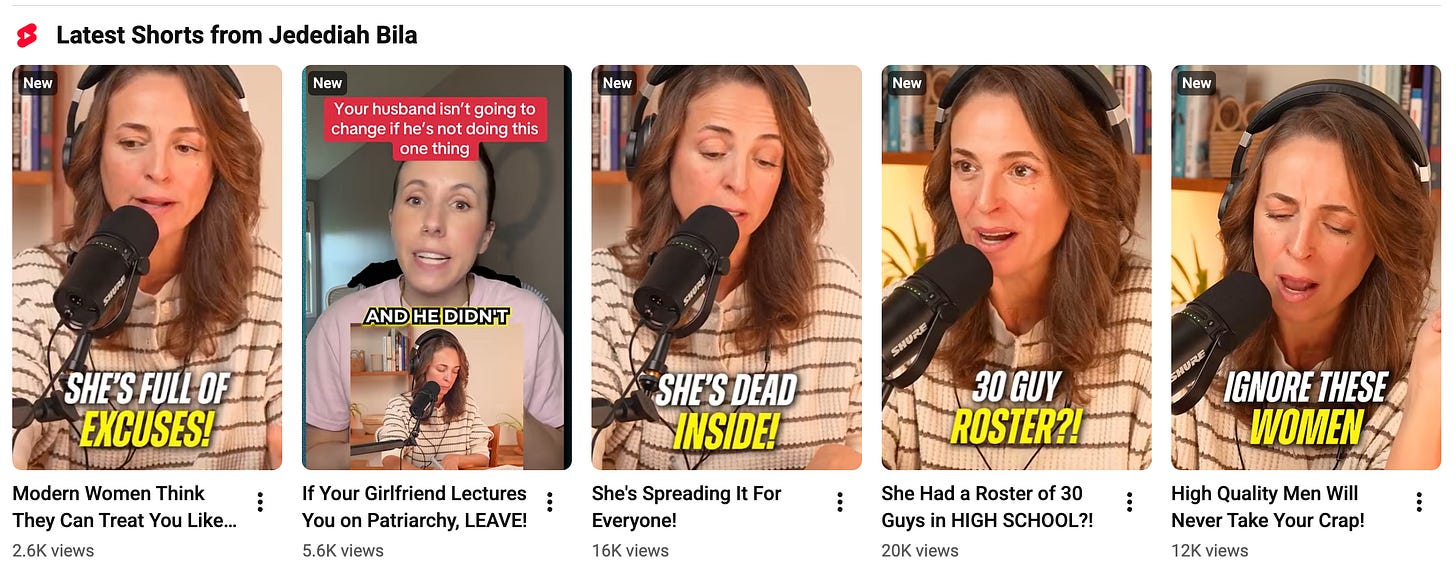

My own feed is a curated mix of jazz videos, chess games, and partisan political discourse. Every once in a while, the algorithm throws in something seemingly nonsensical. I find myself asking: Why am I being flooded with Jedediah Bila shorts? I never heard of her before. There are travel videos here and there, and a creator who claims to be “at the intersection of art and culture.” But again — why am I seeing so much Jedediah Bila?

Sources:

Aleksic, Adam, Algospeak: How Social Media is Transforming the Future of Language, Knopf, 2025.

McLuhan, Marshall, Understanding Media, McGraw-Hill, 1964.

Google Search Quality Rater Guidelines (Updated September 2025)

Jedidiah Bila, https://www.youtube.com/@JedediahBilaOfficia

Join the digital continuum — support this work with a coffee.