The week before Labor Day 1963, the film “Beach Party” played at the Times Theatre on Broadway in Seaside. “Operation Bikini” played at the Sunset Drive-In.

The Oregon State Fair opened in Salem on Friday, Aug. 30, offering “more to do, more to view,” and featuring Jimmie Rodgers in person “with an all-star cast for the revue,” performed twice daily. Governor Mark Hatfield was there to attend opening ceremonies.

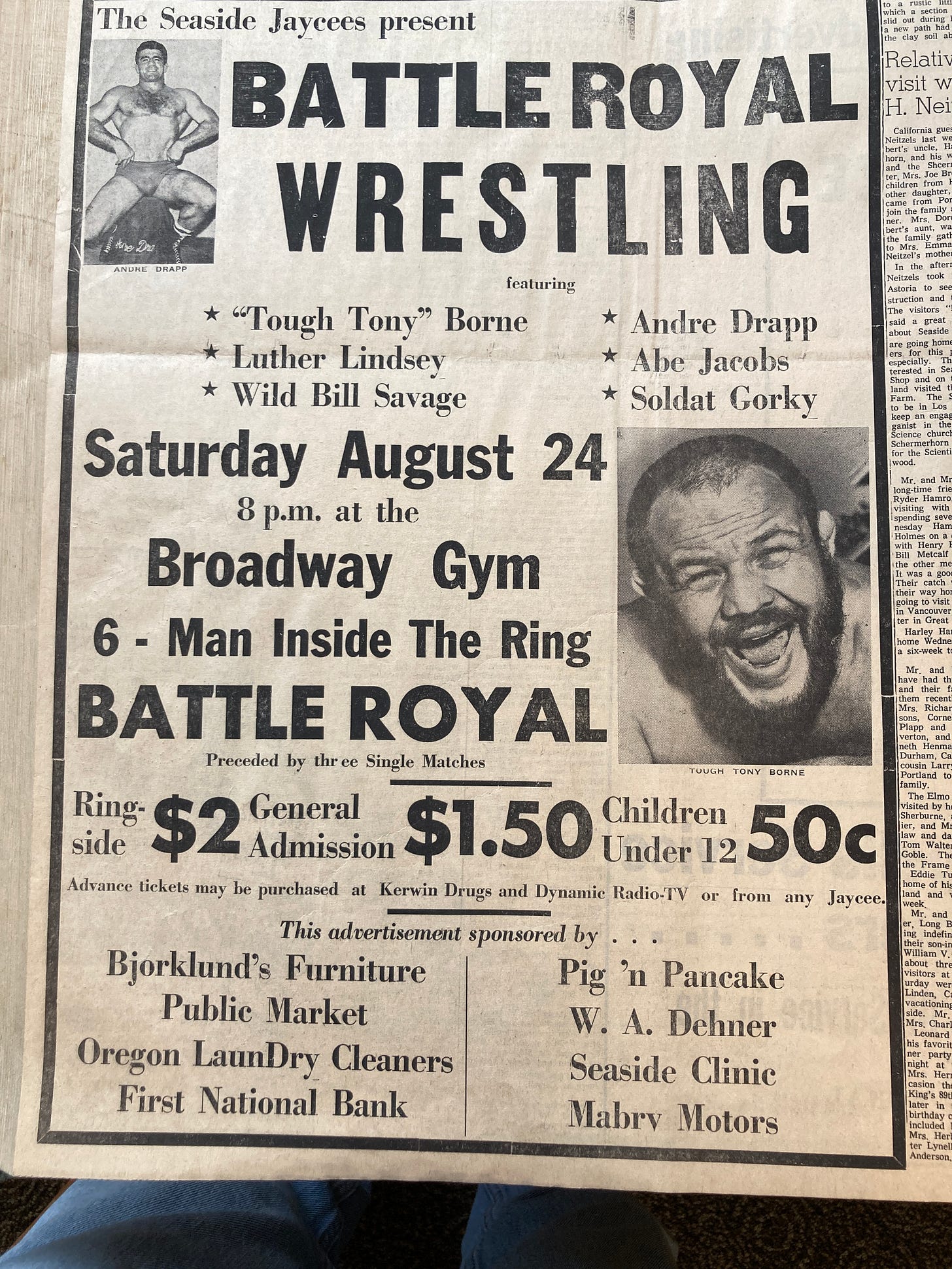

Six wrestlers filled Seaside’s Broadway gym for a “Battle Royal,” featuring Tough Tony Borne, Luther Lindsey, Wild Bill Savage, Andre Drapp, Abe Jacobs and Soldat Gorky — with six men inside the ring.

Six wrestlers filled Seaside’s Broadway gym for a “Battle Royal,” featuring Tough Tony Borne, Luther Lindsey, Wild Bill Savage, Andre Drapp, Abe Jacobs and Soldat Gorky — with six men inside the ring.

Paul Revere and the Raiders were a Northwest sensation in 1963, and were scheduled to perform in Seaside over the Labor Day weekend.

With a base in Portland, recalled James Manolides, a Pypo Club regular and lead man of James Henry and the Olympics, the Raiders, things began to click for the Raiders, with gigs along the Oregon Coast, in Seaside, Cannon Beach and Newport.

While they had yet to become national hitmakers with their No. 1 hits “Hungry,” “Kicks,” “Good Thing” and “Just Like Me,” the Raiders had a Billboard chart hit with “Like, Long Hair,” in 1961, and their version of “Louie Louie” was recorded the next year.

Paul Revere rejoined the band in 1963 after a stint in the military, teaming up with vocalist Mark Lindsay. In May, they signed with Columbia Records, with a line-up including Paul Revere, Lindsay, Phil Volk, Drake Levin and “Smitty” Smith.

“It was really kind of the culmination of where the Raiders hit the so-called ‘big time’ in the Northwest,” Mark Lindsay said in an interview.

‘Driver courtesy’

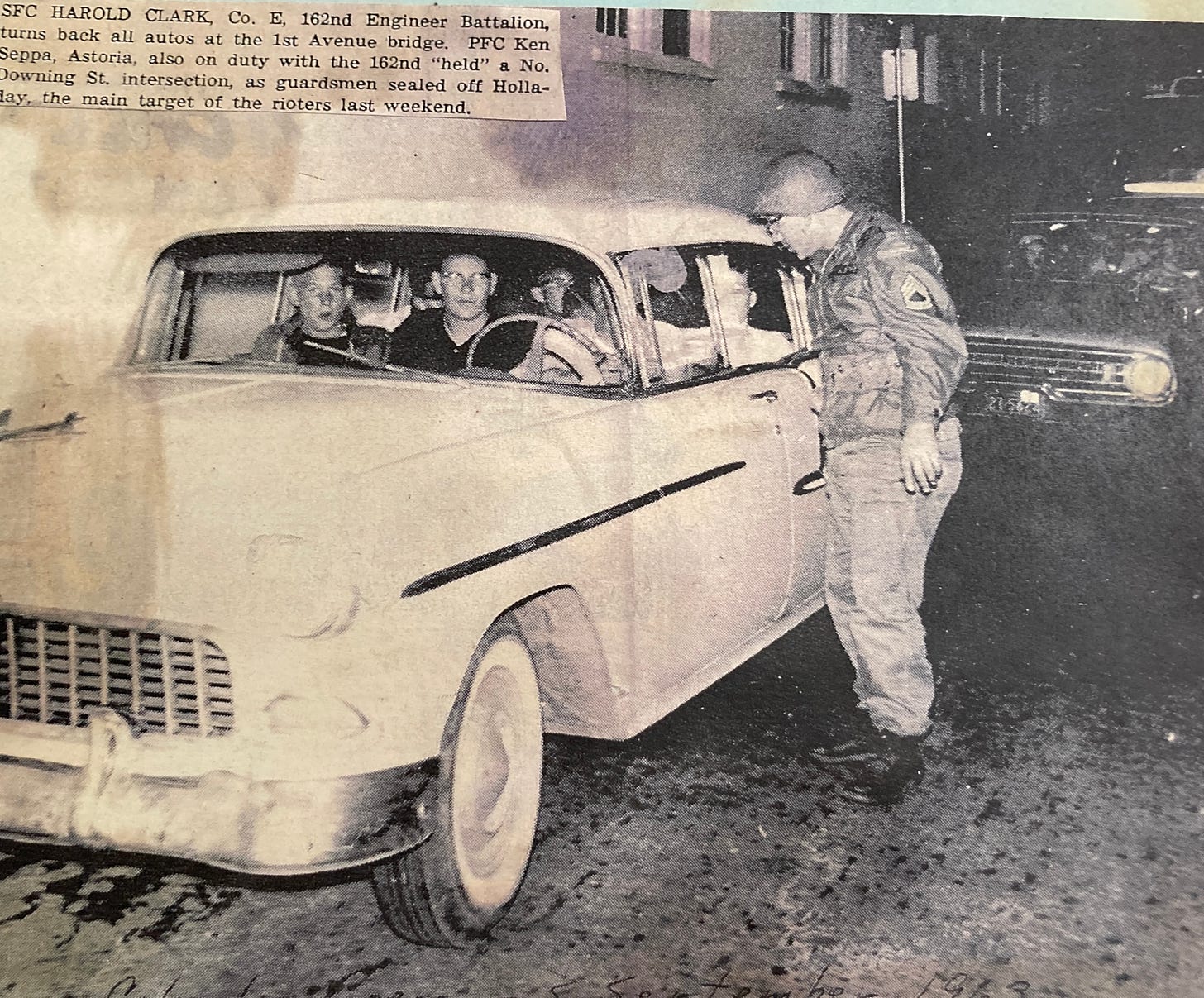

At Camp Rilea, north of Seaside, amphibious national defense assault training exercises unfolded on the beaches. The practice brought 1,000 troops from Puget Sound to the Columbia for the training program.

The prospect of an “unusually large crowd” in Seaside for the Labor Day weekend loomed with a five-day forecast indicating higher than normal temperatures and little or no precipitation.

“The fact that weather has prevented many weekend trips for the average family this summer will serve as an added inducement for travel during the coming weekend,” the Signal reported on Aug. 29.

Crowds had been orderly all summer, the weekly announced with cautious optimism. “The element which has always caused trouble here has either been absent or careful of its conduct. There has been far less police activity during the summer than in previous years. Local authorities do not anticipate anything different during the coming weekend.”

Seaside Police Chief Ken Healea focused on driver courtesy. “If a car appears uncertain as to whether or not to turn,” he said, “it may be because the driver is unfamiliar with the street or route he plans to take and blowing a horn impatiently will not solve the problem.”

The city perhaps would have been wise to remember the words of visitors in 1962, after the first weekend of holiday riots.

“Sure, we’ll be back next year,” students told the Oregon Journal the previous September. “We won the war, didn’t we?” they added, considering it an “official capitulation to power” when the Tacoma-based rock group the (Fabulous) Wailers took to the roof of the Pypo Club to pacify the crowd.

Saturday, Aug. 31, 1963, broke “cold and damp but lively,” Peter Tugman wrote in the Oregonian. as a crowd of 2,000 students jammed the beaches and brought a new sport, surfboarding, into Oregon. There was singing, dancing, necking and beer drinking. It looked like a happy switch on last year’s ugliness.”

In their report the following week, the Signal offered this assessment of Day One:

“The trouble began Saturday afternoon and evening when large numbers of youngsters, obviously drawn by the excitement, gathered in large numbers on the block between Columbia and the Turnaround. The mood was one of recklessness rather than belligerency. There were few indications of drunkenness, and drinking, unlike last year, was of little importance.”

Probably not more than a handful of the youngsters present had any idea of causing trouble, the Signal wrote, but a small group of leaders “constantly agitated. … We are talking about the hard core.”

The very presence of the crowd constituted an explosive situation, which could be triggered by the slightest error in judgment on the part of the police at the same time it was impossible to move the crowd.

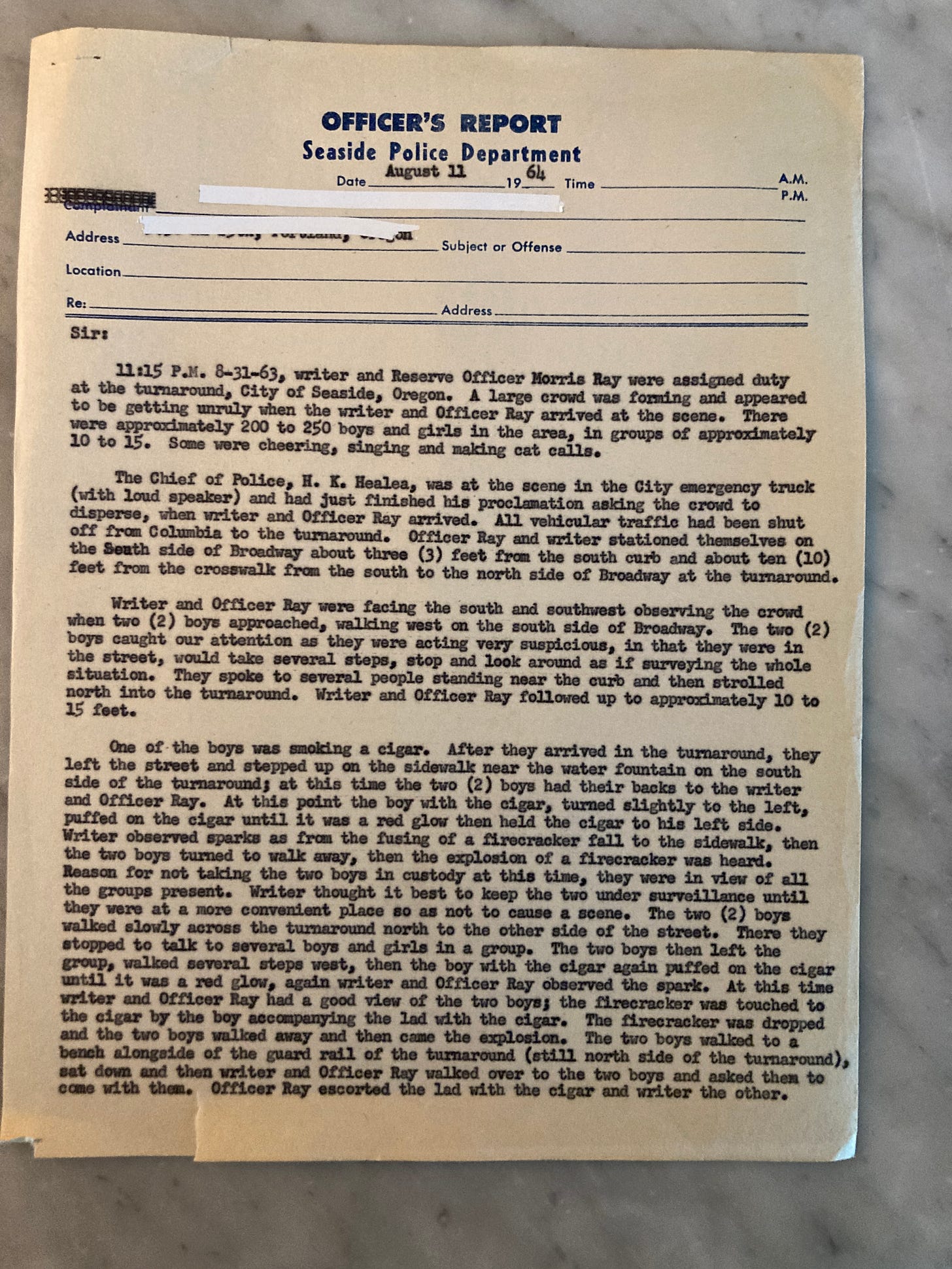

Seaside police patrolman Ottie E. Nabors, in an officer’s report delivered almost a year later, Aug. 11, 1964, described the timeline in detail.

Nabors and reserve officer Morris Ray were assigned duty at the Turnaround. A large crowd of “approximately 200 to 250 boys and girls in the area, in groups of approximately 10 to 15 was forming and appeared to be getting unruly. Some were cheering, singing and making catcalls.”

According to Nabors, Healea was at the scene in the city emergency truck with a loudspeaker, and had just finished his proclamation asking the crowd to disperse when Nabors and Ray arrived. Ray and Nabors stationed themselves on the south side of Broadway at the Turnaround.

“One of the boys was smoking a cigar,” wrote Nabors. “After they arrived in the Turnaround, they left the street and stepped up on the sidewalk near the water fountain on the south side of the Turnaround. The two boys had their backs to the officers.”

At this point the boy with the cigar turned slightly to the left, puffed on the cigar until it was a red glow, then held the cigar to his left side.

The two officers observed sparks “as from the fusing of a firecracker” falling to the sidewalk. The two boys turned to walk away before the explosion could be heard.

Nabors, rather than take the two boys into custody in the midst of the crowd, kept the two under surveillance “until they were at a more convenient place so as not to cause a scene.”

The two boys walked slowly across the Turnaround north to the other side of the street, Nabors wrote in his narrative, where they stopped to talk to several boys and girls in a group.

The two boys then left the group, walked several steps west, before the boy with the cigar ignited another firecracker — a term that described everything from sparklers to cherry bombs.

“The firecracker was dropped and the two boys walked away and then came the explosion.”

When the two boys sat down on a bench alongside the guardrail of the Turnaround, the two Seaside officers asked them to come with them.

After crossing the street to the north side to the Seasider Hotel, police asked the boys for identification. Police asked what was the reason for exploding the firecrackers.

The boy stated that the firecrackers had been given to him by another boy.

While in the Seasider Hotel lobby waiting for the police car, several other boys appeared and wanted to know what the matter was, and why their friends were being detained. Police informed them that the two boys were going to be taken to the police station.

When officers arrived, a large group in the parking lot on the east side of the hotel. The boys were taken into the back seat of the waiting police car as the other boys outside the car “broke up and ran in all directions.”

On the way to town the two boys stated that they had just arrived in town and had parked their car on South Columbia, near Vern’s Arcade. “They stated that they were in town just to observe what was going on,” police reported.

The two boys were booked and placed in jail.

Nabors returned to the Turnaround immediately, due to the shortage of police officers, as rocks and bottles started flying. Tower is target

The Signal’s account of the night listed at least three attempts by police to clear the crowd, describing two previous visits by Police Chief Healea in a personal plea for the crowd to disperse, both without avail.

He read over the loudspeaker system the legal statement:

“As follows in furtherance of my duty to defend my country against those who by riot or otherwise endanger the public police peace, of safety and by virtue of the authority conferred upon me, I, as chief of police, command you in the name of the state of Oregon to disperse.”

The response, wrote the Signal, was a wave of boos, hand-clapping and explosions of giant firecrackers. Healea returned in the police truck for a third time before midnight.

The lifeguard tower had been the focal point of the 1962 riots, perhaps a metaphor for ownership of the beach, or a way to buck the authorities. Perhaps it was just a handy weapon. The group had disassembled the 30-foot tower, dragging it over the beach wall to the Turnaround onto Broadway.

One year later, the tower — which had been replaced by the city, approved by council at $100 — was the target again.

The first attack on the tower was stalled by the police and firemen. But as the mob spilled onto the street, they took control of the area to topple the tower. From there, in a military-style formation of their own, tipped over the tower and used it as a battering ram, from the beach to the Turnaround before marching down Broadway, Seaside’s main drag. Mayor Pysher was absent Saturday night, the city led by City Councilor Vern Davis as acting mayor.

Davis instructed the police detail at the Turnaround to give up the tower rather than risking injury or incident in the attempt to save it.

Wrote Silvie Andrews in the Oregon Historical Quarterly: “Members of the throng charged back up Broadway, ripping out power lines and leaving shattered storefront windows in their wake.”

Others broke the slats out of public benches for clubs and firewood.

The Oregonian reported the resulting melee moved through a series of sharp skirmishes, with 10 or 20 arrests and culminated with the students’ first organized assault.

“As night fell, trouble built up fast. A crowd of 600 teenagers jammed the Pypo Club, an under 21 establishment rock ‘n’ roll and folk songs. Another 200 tried to crash the gates for the privilege of paying $1.50 for dancing to the raucous tunes inside.

Police quickly broke up the disturbance and the kids spilled out on the street. The mood seemed jovial but appeared to crystallize when Seaside police chief Ken Healea pulled up in a sound truck and asked, ‘You want to start a riot? You’ll be treated like rioters.’ He slammed the truck into reverse and backed out at high speed. On cue, squads of firemen, Seaside police and reserve police officers converged on the Turnaround swinging axe handles.”

Recalled the Raiders’ Mark Lindsay: “That year the city fathers decided they were gonna walk through the town with ax handles and knock the brains out of any kid that looked like they didn’t need to be there, so it was kind of brutal.”

The city’s acting mayor, Vern Davis, informed Nunn and Oregon State Police Superintendent Maison about 11:30 p.m that the situation was worsening. Nunn informed Governor Hatfield — still at the State Fair in Salem — of the situation and the governor agreed that the guard should be used if necessary.

The Oregon Journal reported more than 2,000 young people “terrorized” the downtown area Saturday night when a series of scuffles with police through the evening erupted at midnight into a full-scale riot.

“Hundreds of them were driven onto the beach by police wielding ax handles. Seaside police, augmented by all available reserves and volunteers were able to disperse the youths. They chased the mob back onto the beach. Estimates range from 1,500 to 2,000 young people; the rioters used benches from the Turnaround to build a huge bonfire on the beach.

Police, aided by volunteer firemen, quickly regrouped and charged the mob with axe handles and night sticks. The crowd scattered and started to disperse marking the beginning of the end of the riot.”

Local police and volunteer firemen put down this disturbance in about 45 minutes, UPI reported, although groups were still being broken up as late as 2:30 a.m. Sunday, Sept. 1.

Coming soon: Day 2, Sept. 1, 1963: The city erupts.

Great to follow this historical story. Keep up the impactful writing!