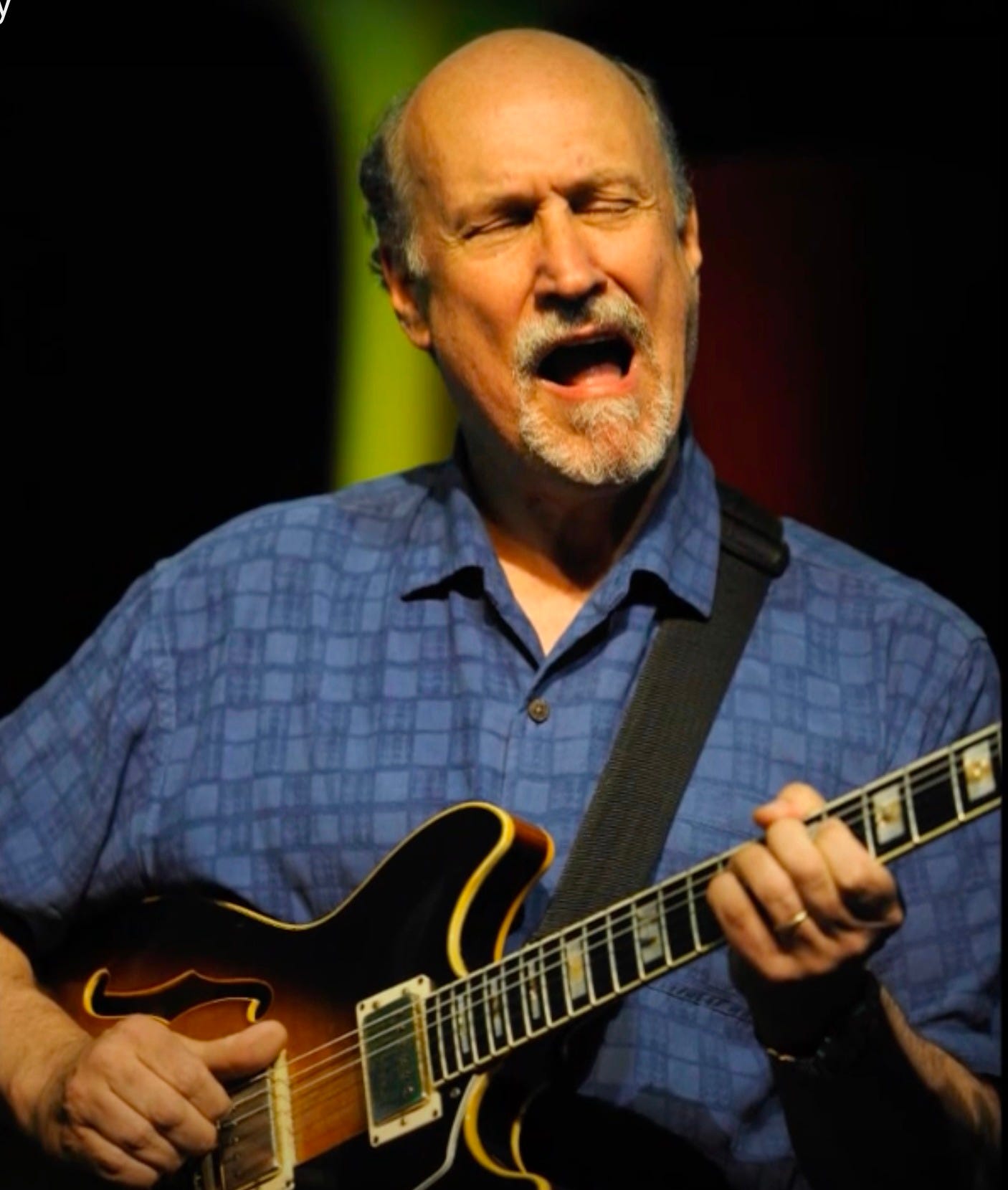

An Interview with John Scofield, Part 2

'I’ve given up trying to figure out who I am'

Q: I’m going to switch the conversation a little bit to your repertoire over the years. I just read an interview about your time with Miles, where he would take your riffs, and he turned one into a song.

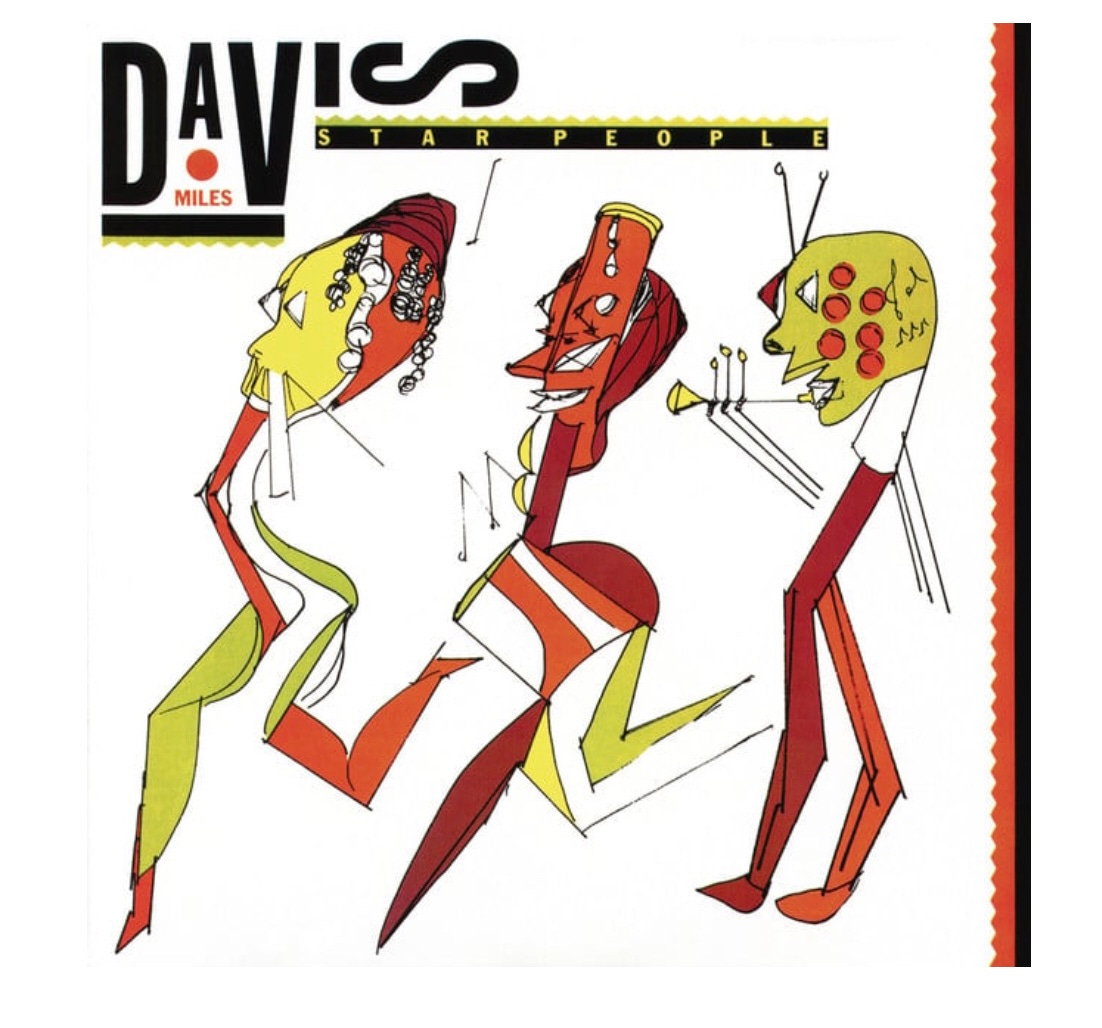

SCOFIELD: There’s a few of them. There’s a few on the record Decoy, and one on the record Star People before that, and on another album called You’re Under Arrest, which was the title tune, which is the tune I wrote. And Miles was doing that, not just with me, but with Bill Evans, the sax player, and with his own solos. He would listen to gigs or rehearsals and hear us jamming on one chord, just jamming away, and he would like one little part, and he would have somebody, believe it or not, Gil Evans, the great arranger, transcribe this little line, and then we would play that in unison, and in some instances it was my solos that he liked.

Q: Did you get credit for that?

SCOFIELD: I did get credit. I think the first one I didn’t get credit for, and he invited me to his house and had some chords, and Gil was playing the bass line, and I improvised, and he said, play, improvise, and he recorded it,. Then he said, “OK, that’s it,” and then I went home, and the next day we went in the studio, and Gil had written this line out over these changes for us to improvise on. It’s called “It Gets Better” on the record Star People, and I don’t think I got credit for that one, because Gil came up to me and said, “John, you know, that’s your solo from yesterday,” and Miles heard him say that, and Miles goes, “Gil, he’ll get a big head.”

Q: Tell me about Miles.

SCOFIELD: He was, I guess, the only person that I really hung out with who was a superstar, because he transcended jazz. He came at this time in American history, and he was movie star handsome, and he was great, and his music spoke to a lot of people outside of jazz, because he could play so beautifully. He was a brilliant strategist at getting the music out there, but still playing what he considered great, and important jazz music, because he loved that. So he was all that, but the guy was a superstar. He couldn’t go outside his house because people loved him and would bug him.

Q: You left him — you chose to leave him at a certain point.

SCOFIELD: I quit because I thought he was getting sick of my playing. He kept playing me records of Eddie Van Halen, and I can’t play like that. Eddie Van Halen is amazing. But I had a chance, because during the time I was in his band I had made a couple of albums that had really been successful, and so I had a chance to get a lot of jazz festivals and gigs with my own group, and I was really ready to do that. So it was a good thing.

Q: At that point, I think it’s interesting that you had two hits with Miles, in the Cindy Lauper tune, “Time After Time,” and the other ... was it a Michael Jackson song?

SCOFIELD: “Human Nature.”

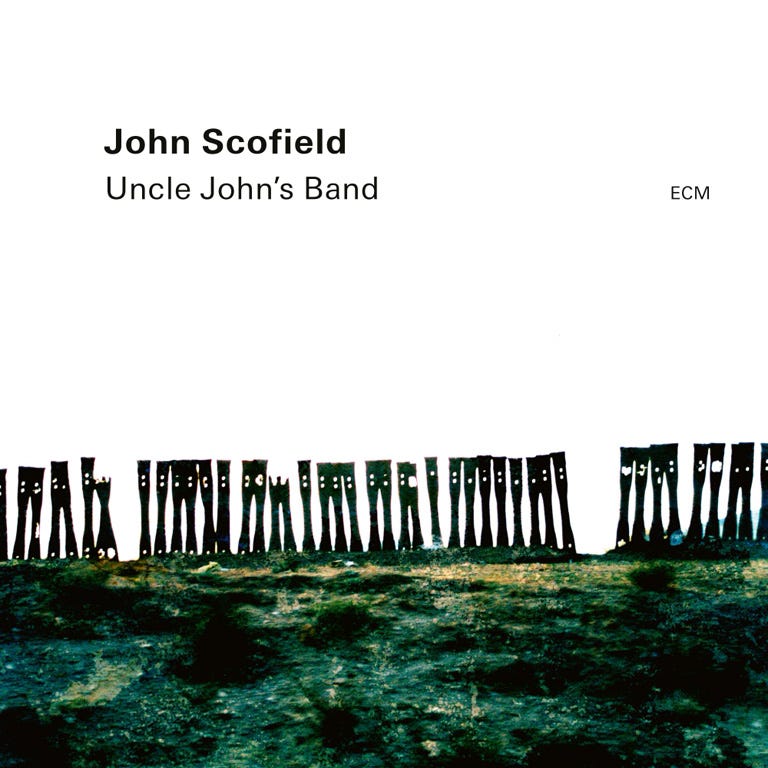

Q: Now, your most recent — is it your most recent LP, CD, whatever, what do we call it now? A record?

SCOFIELD: Whatever they’re called. Uncle John’s Band. We did some Grateful Dead tunes and a Byrds tune, a Dylan tune.

Q: So are you going back to pop... I know you’ve always loved pop music?

SCOFIELD: If you listen, we totally jazz out on them. It’s another vehicle to play. But I do like the songs. I can’t play it if I don’t like the song. “Mr. Tambourine Man” is a good example. It’s simple, right?

SCOFIELD: Really simple, yeah. Three chords.

Q: But it’s hard to make those songs sound interesting when you’re improvising, isn’t it?

SCOFIELD: Well, on “Mr. Tambourine,” we let go of the changes and kind of played free, with that jazz-rock feeling, we played completely free. The bass player might go somewhere, I would go somewhere, it was completely free. We didn’t stick to a Bob Dylan form.

Q: Sort of reminds me of Coltrane, you know, playing on “Chim-chim-cheree.”

SCOFIELD: Jazz musicians can kind of make jazz out of almost anything. You’ve got to find something that somehow feels good to play and hopefully maybe people will like it. It’s really nice. A melody that you like. It can be from anywhere. It could be from classical music. It could be from pop music. It could be from folk music.

Q: When you left Miles, you went another direction. Would you call it avant-garde or “new” music?

SCOFIELD: Because all of us that are “our age” grew up at a time when free jazz was around, fusion was around, the old beboppers were still around. So, you know, I was aware of free jazz and tried to play it with my friends and stuff. But over the years I’ve done some things that are more associated with what might be called avant-garde.

Q: And now you’re back with ECM, the record label, which was — tell me about ECM.

SCOFIELD: I haven’t been on ECM before this. I was on Enja — the other label from Munich, Germany. ECM is Manfred Eicher, and it’s an incredible label that’s always been really artistically oriented. Some people didn’t like it because he didn’t do as much really straightahead jazz. But he did a lot of great, great stuff, Keith Jarrett, incredible music. He’s a real music guy, and he’s still going. He’s in his 80s, and he still has ECM records, and there are very few record companies left.

Q: How would describe the record label’s concept?

SCOFIELD: Manfred Eicher hasn’t physically produced the records that I’ve made for ECM. I’ve made them myself and paid for them and then sent them to him, and he says, “Oh, OK. We’ll put this out. Why don’t you use this song first?” Sometimes he’ll say, “I don’t think that song makes it.” I always record enough so that we can ditch a tune or two. And he produces it at the end and he supervises how the sound is. It’s great.

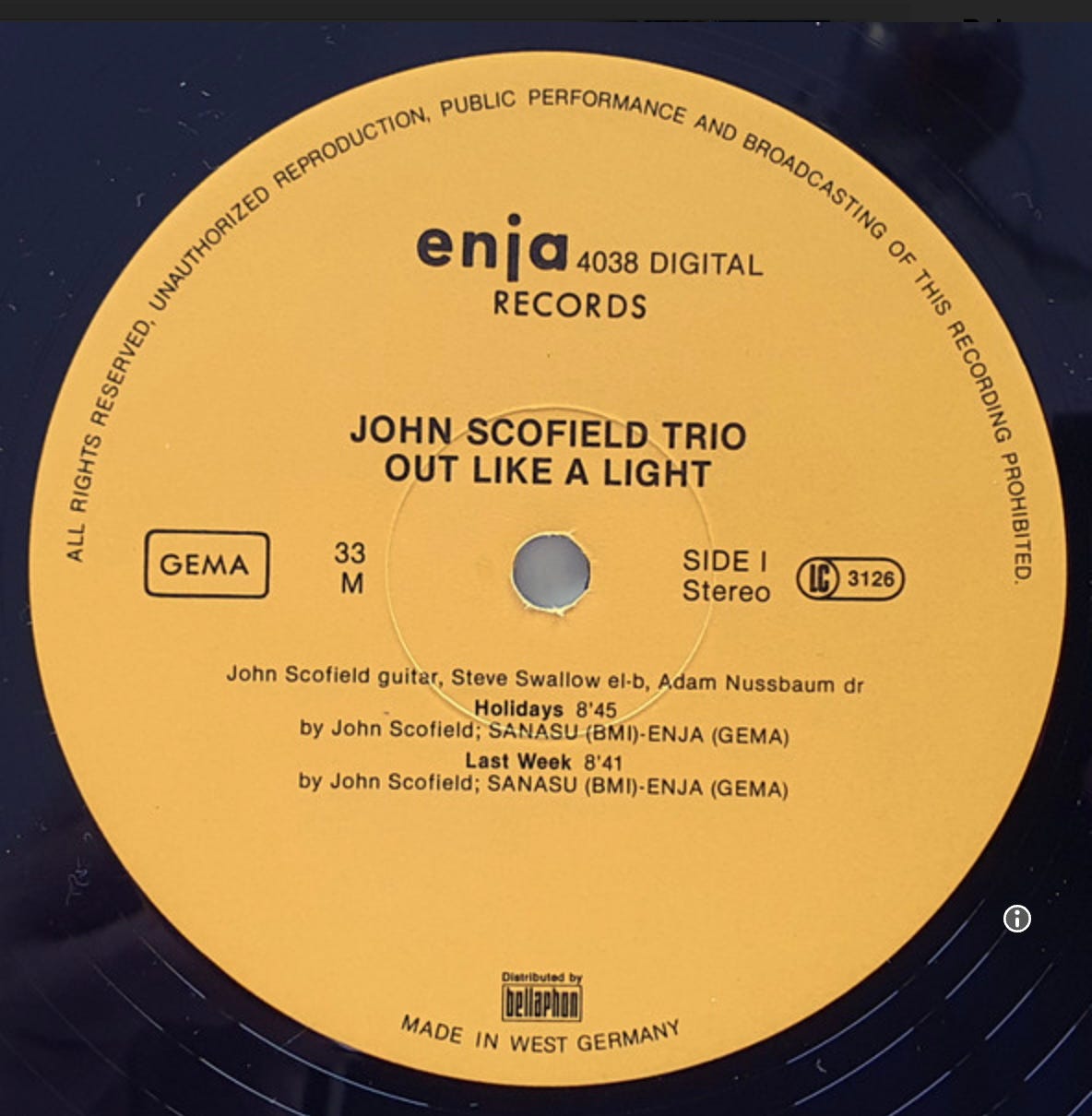

Q: And Enja was, what, a similar type of label?

SCOFIELD: Well, that was back when — and ECM used to do this, too — those producers from Europe would come to America and record in New York. Manfred, who’s in his 80s, doesn’t want leave Europe to record in New York, he wants to record in Europe only. Matthias Winckelmann would come to New York. Sometimes I’d be on tour and we’d record in Europe also and he’d come to the sessions and be there too. He was a real open producer to whatever the artist wanted to do. He liked everything. There was one take where we actually stopped and didn’t even finish the tune, and we fucked up the ending. Afterwards, he said, “You know what, that’s OK, it’s great!”

Q: You developed an international audience over the years and you’ve been so eclectic since then. Do you ever confuse yourself sometimes?

SCOFIELD: I’ve given up trying to figure out who I am. I like playing the funk. I like playing free jazz. All my life I’ve been trying to learn how to play modern jazz and continue to do that, and to analyze that. Just working on the guitar. I know it has been eclectic and that’s been fun, getting to do all that different kind of music.

Q: I remember you were out in Portland in 2020. In February 2020, wasn’t it, when the pandemic hit.

SCOFIELD: I was in Portland when, yeah, the pandemic hit, I went home and that was it, no more.

Q: Because they were making a movie, which of course came out, but it does seem abbreviated, you know, to a degree.

SCOFIELD: We were playing at the college (Lewis & Clark) there and then everything shut down. It was nice to be home for the two years.

Q: So there were a lot of musicians that built up their chops over that time, huh?

SCOFIELD: Yeah, a lot of practicing. People complained because they couldn’t play gigs. It was difficult for a lot of people. For me, being in my 60s or almost 70 when that happened, I was ready to stay home, you know? I’d been on the road for 50 years.

Q: You say the record companies are gone? Is that right?

SCOFIELD: Oh yeah, not like it used to be.

Q: So how do jazz players make their meager living, so to speak?

SCOFIELD: I don’t know. I don’t know how young people are gonna do it. Jazz education has become an industry all its own, I guess.

SCOFIELD: People go to school and get their masters and then start teaching other kids and the whole time wanting to play, and just play when they can. So the music survives. It’s just different. I feel like I’ve been lucky that I haven’t had to teach, although I’ve done a fair amount of it. I haven’t had to do that. I’ve had gigs and I feel like the gigs have what made me able to play some jazz, you know?

Q: What are you working on?

SCOFIELD: Well, I just got done mixing a record, the duo record I made a few months ago with Dave Holland. That’s really nice, I think. And that’s gonna come out in half-a-year on ECM. I’m putting together a new kind of funky group with some guys, John Medeski, who I played with a lot, and the bass player I’ve been playing with on my last few records, Vicente Archer.

He’ll be funk with upright. And a really good drummer who lives in Seattle, Ted Poor, who I just met and played with, and he’s really versatile. I’m excited to play with him.

I still got my trio with Bill Stewart, you know, who I’ve been playing with for 30-plus years. Steve Swallow’s staying home now more because he’s 84. So Vicente’s been playing bass. And I keep playing with all these guys.

I’m doing a bunch of things with the London Symphony Orchestra with a new piece by Mark-Anthony Turnage. It was commissioned by Sir Simon Rattle. We played in London, Paris, and Luxembourg.

I’ll go back to Europe with my trio, with Bill Stewart and Vicente Archer, for the March, April run. We’ll play Paris then. New Morning, we always play the New Morning in Paris. It’s a nice big club, yeah.

Q: What do you see, do you see, as you travel, I mean, do you see regional jazz scenes everywhere you go?

SCOFIELD: Yeah. Just like here. There’s good players in Oregon, there’s good players all over. And, you know, more in the urban areas, because they don’t like jazz in a lot of places because they don’t know nothing about any jazz. They’re so far removed from that.

Q: Fortunately your audiences are hip to your music going in?

SCOFIELD: Somewhat, or curious about it, yeah.

Q: Do you find backlash from jazz audiences that don’t want to hear Grateful Dead?

SCOFIELD: Yeah. There’s always like a couple of irate-looking guys along most of the other people who are totally cool with it.

Q: There’s lots of you on YouTube.

SCOFIELD: I know.

Q: Have you watched? I mean, where should somebody start if they’re familiarizing themselves with your music?

SCOFIELD: You know, Rick, I don’t even know. Just look down my discography, and, you know, my more recent stuff. The earlier stuff, I don’t think I had it together. But maybe I’m fooling myself. But I like the last few records I made on ECM. If you like funky-type stuff, there’s a record I made that was successful, called A Go-Go, with me and the band — Medeski, Martin, and Wood — and people who know it like that.

You hear that a lot, and especially I’ve heard it in all sorts of places.

SCOFIELD: Yeah, because somehow that broke through a little bit..

Q: OK, cool, man. All right, thanks, man, for making the time.

SCOFIELD: Oh, you got it, thank you for thinking of me.