Q: Let’s get right into it. What effect does all this political turmoil have on your touring life and jazz life, if any?

SCOFIELD: Well, it just kind of started since the election, I was in Europe when the election happened. I had just gotten there. It seemed like... A lot of people had this reaction, like, “How can you be from that country?” “What’s with your country?” It used to be “Isn’t he terrible.” Now people are really worried.

Q: Do you think it’s going to affect your travel in the future?

SCOFIELD: Not at this point, but we’ll see. It could. Europe could really get destabilized.

With America screwing up NATO, that would really mess up all the jazz gigs for all the jazz musicians.

Q: I know you’ve been traveling internationally for decades. This is one way we communicate with people around the world, isn’t it? You’ve played little cities everywhere.

SCOFIELD: Really all over Europe. That’s where the interest is. Asia loves jazz. Wonderful audiences, especially in Japan and Korea, who are somehow aligned with the USA. It’s really Europe, European culture and appreciation for the arts, that tradition. I’m sure it’s the same for dance, theater and visual arts.

Q: And Russia’s big into jazz.

SCOFIELD: Yes. It’s a terrible thing that’s happened. Because we played there a couple of times. It was fantastic. You know, in the cities. In St. Petersburg and Moscow. But what I’m told is there’s this huge backwoods element in Russia. And that’s who are really supporting the weirdness. And it’s similar to here.

Q: Did I hallucinate, but are you from New Orleans originally?

SCOFIELD: My mother’s from New Orleans. I’m from Connecticut. My mom was a New Orleanian. Born there a long time ago, too. Because she was old when she had me. She was born in 1909.

Q: So did she have any of that New Orleans sensibility?

SCOFIELD: Yes. She was Southern through and through. And even though she lived up north for probably 45 years of her life, she still had a southern accent. She liked jazz music. Especially the old guys. Louis Armstrong, and she loved Pearl Bailey and Ethel Waters. But she was no jazz aficionado by any means, and wasn’t really into it at all. But she called Dixieland music “the music they played out by the lake.” And that’s what they say in jazz history, that jazz was played by black jazz bands at Lake Pontchartrain at the park by the lake. I always thought that was weird that she said that. And other than that, I have really no family affinity to the birthplace of jazz other than they’re from there

Q: Over your career, you’ve spent a lot of time recreating some of that New Orleans sound.

SCOFIELD: I always loved New Orleans music and New Orleans R&B, too. As well as jazz. The rhythm — the rhythm that became swing music a long time ago. And that rhythm from the second line bands being from the funeral tradition — playing happy music on your way away from the funeral, you know. That’s dance music, and that beat from the New Orleans brass bands, and that transferred over to jazz. That same beat, those drummers that played the early R&B records knew that rhythm, and it seeped through in their rock ‘n’ roll playing.

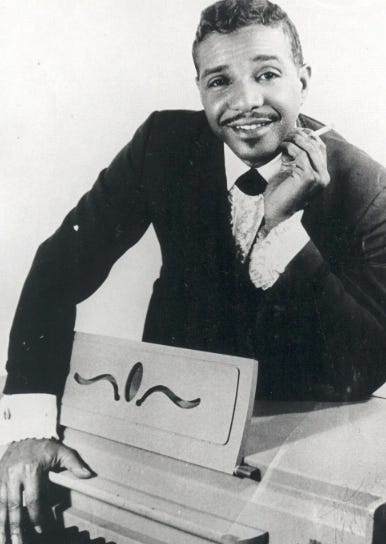

Q: Dr. John is another one that you have a musical relationship with.

SCOFIELD: Yeah, I played with Dr. John, knew Dr. John. And I’m a good friend of George Porter from the Meters, the bassist. And I know Zigaboo Modeliste, the drummer. Yeah, those guys, forget it. And Dr. John was just a wealth of knowledge. To get to hang with him and hear all about it kind of firsthand, because he was even around in the ’50s. When he was a kid, he would hang out at the recording studio, Cosimo’s Recording Studio (Cosimo Matassa’s J&M Recording Studio in New Orleans), he got to witness incredible piano players like Huey “Piano” Smith.

Live at Carnegie Hall

Q: Your first regular jazz gig was with the baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan, right?

SCOFIELD: You know, I went to Berklee (College of Music) right after high school, and I was up there for a couple years trying to get it together, practicing it, and eventually got to play with the good players. And then I dropped out of school because I could get enough gigs around town to support my meager existence. And me and Dave Samuels, the vibes player, got called to play for a week with Gerry Mulligan at the Jazz Workshop to augment his quartet. And that was Alan Dawson, the great drummer, who got us on, because he knew Gerry. Gerry liked us. He picked us up to be in his band. A few months later we made Live at Carnegie Hall with Chet Baker and Gerry Mulligan. That was in November ’74.

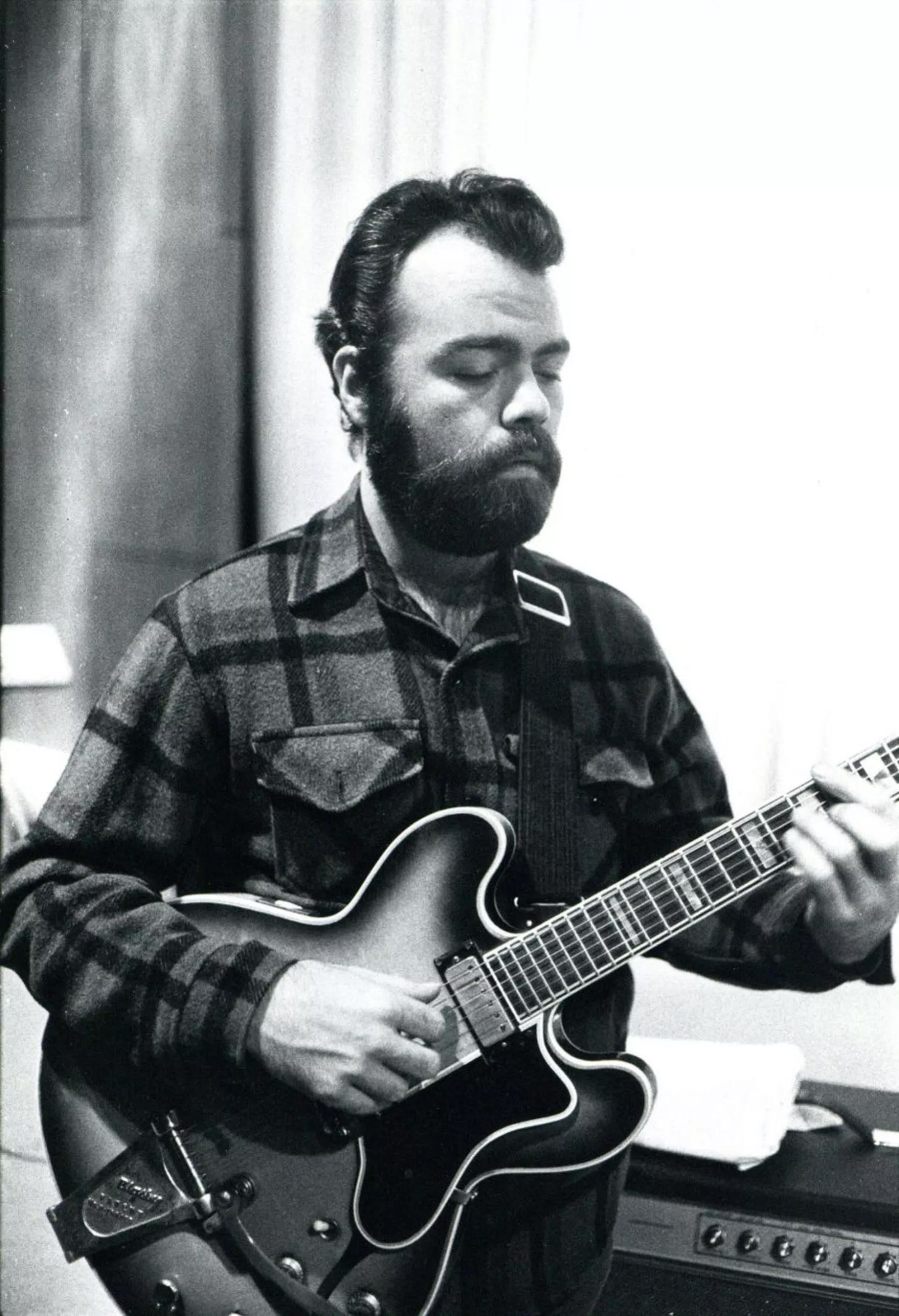

Q: When did you start your path outside of the bebop tradition?

SCOFIELD: Well, you know, this was the fusion days, jazz fusion. It had come together. Miles had made Bitches Brew, and all of a sudden there were all these bands like Mahavishnu Orchestra, Weather Report. And right when I was playing with Gerry Mulligan, I met Billy Cobham. He invited me to be in his band, which was a huge thing for me. That allowed me to leave Boston, move to New York, and join Billy’s band.

Q: That was Spectrum?

SCOFIELD: Yes. At one point, it was called Spectrum.

This was his horn band at first with the Brecker Brothers. And then he started a quartet the second year I was with him, with George Duke and Alfonso Johnson on bass.

Q: So you were playing with Michael and Randy Brecker?

SCOFIELD: At first, yeah. Wow. And they were incredible. You know, I mean, they became my idols. Before that, I had met Gary Burton and Steve Swallow and played with them. They were my idols. And then I met Mike and Randy, and holy shit, did they play. And they were beboppers too, even though we were playing fusion. I just picked Mike’s brain about Joe Henderson, and I loved Randy’s compositions.

Q: Did you feel technically accomplished at that point?

SCOFIELD: No, not at all. I felt like I was a little bit in over my head. But I was practicing like crazy.

Q: Does every jazz musician at the top know how to read?

SCOFIELD: I think … no. There are some guys from the old days who I’ve been told can’t read. George Benson, who’s one of the greatest, most swinging bebop guitar players that’s ever existed, I was told doesn’t read. I think most horn players, just to learn the instrument, there would be some book of notes. But guitar players can sometimes just learn by ear. They’re coming from a different tradition almost. I was told Michel Petrucciani, who was a really wonderful French jazz pianist, I was told he didn’t read.

But I think it’s so different from classical music that you read to learn a song, or you read to be good enough to play in the big band, you learn do that — which can be considerable.

Q: You prefer small groups in general, at least historically, although I’ve heard you play with symphonies.

SCOFIELD: I just did a piece with symphony that my friend Marc-Anthony Turnage wrote. But I play with small groups because that’s what’s available. I actually like big bands and have gotten to appreciate big band writing and everything more as a grown-up, but there’s not that much of that around.

Plus, you know, I mean, if somebody wants me to play their big band job and it pays $25, I’m not going to be there.

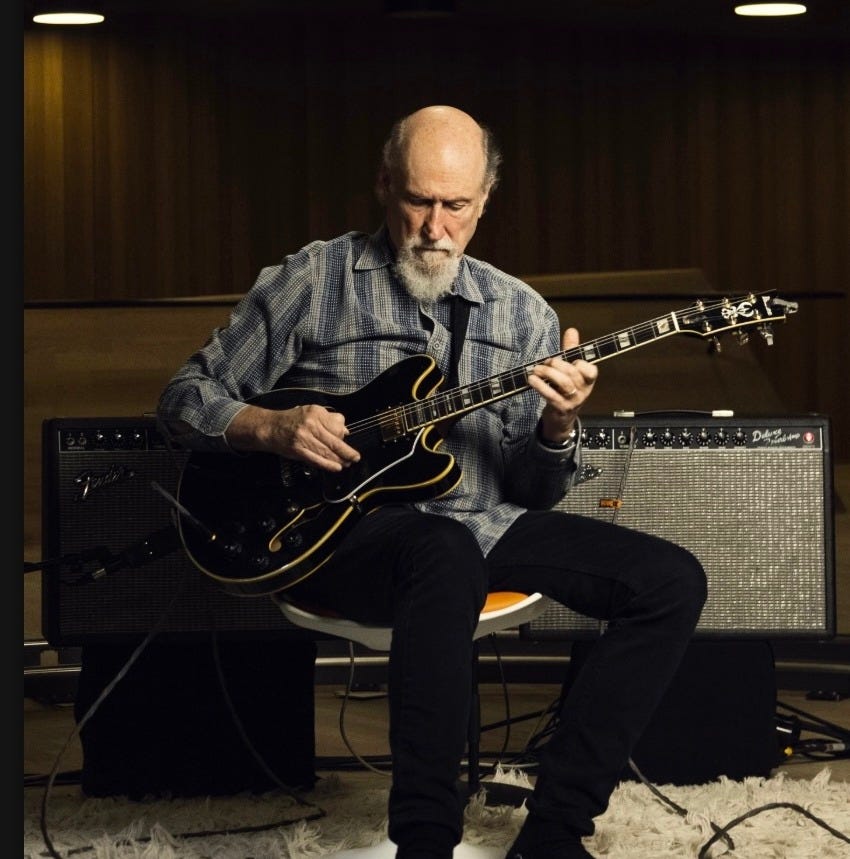

Q: In terms of developing your sound, it seems to me your sound was developed and has been pretty consistent through your whole career. Would you say that’s accurate?

SCOFIELD: Well, hopefully I’ve gotten it a little bit better, you know. I mean, guitar is weird because you get a sound with your fingers on your instrument and then you have to deal with amplifying the guitar. So it’s sort of twofold in that way. But mainly it’s the fingers, you know.

We’re getting a sound out of the string, learning what a string does. If I do have, if my sound is together — which has gotten more together — like the first recordings I did, I remember, I had no idea what I sounded like, and I went back and was like, whoa.

I was around enough people that could get a good sound out of the guitar early on. So that was like, “Oh, OK, that’s what you’re supposed to do.” In real time, not just listening to a record. But when I was in high school, and went to Boston, especially, I went and heard Kenny Burrell and Jim Hall in clubs. And Pat Martino and George Benson and Jim Hall. So I heard really good jazz guitar. And the great rock players: B.B. King, Jimi Hendrix, et cetera. I heard enough in rooms, not necessarily on a record, you know, which was pretty inspiring.

When I went to Berklee, there was this guy, Mick Goodrick, who had a wonderful, beautiful sound. I listened to him a lot because he was playing around all the time.

Q: Was there a point where you felt, this is it, I feel like I’ve got it, I’m going to cultivate this sound and this is who I am?

SCOFIELD: It’s more like I knew what I didn’t want to sound like on the guitar. The sounds that the guitar made that I had to fight. I was not using that stuff and just trying to get just a nice sound. It’s always been a work in progress. It’s always been something you have to think about.

The guitar is a monster that you have to try to tame.

Q: At the same time, I hear so much emotion in your playing. Your emotion has been just a well for you. I mean, do you get cold spots where you just feel like, “I need to take six months, a year off, just refuel myself?” And how do you do that?

SCOFIELD: Well, one thing is, when we study jazz, you know, bebop, which I love, a lot of that’s stringing eighth notes together, which can end up sounding really mechanical. And when I would analyze my favorite horn players and piano players too, they would mix it up. They didn’t play all eighth notes, you know? And what they mixed it up with was melody and rhythm. The guitar, especially blues guitar, is really just like a voice and you get it to sing. So I’ve tried to not lose that and to develop that, which I guess that’s an emotional sound, because it’s like singing.

And if I play emotionally, that’s just when I’m trying to not play a lot of eighth notes. But I keep trying to play eighth notes because I freaking love that.

Q: So what we think is emotion is you like saying, “OK, now I need to put a triplet in here?”

SCOFIELD: Yeah, kinda. And riding the groove, you know? When you, you know, you’re letting the song come out of you. Ba da ba boo ba de dot, bop, diddle-la-diddle-le dot, bop-doo-bop. So I’m not really thinking that there would be a triplet or a bop or an anticipation. I’m just letting it happen. I’ve listened to so much jazz, all my life. That’s inside you. And then you get that to come out on your instrument.

Q: Do you practice every day?

SCOFIELD: Some days I don’t, but I should do it every day. The more I practice, probably the better I am. But I think some days you can get more out of 15 minutes than you can two hours the next day.

Q: How is that?

SCOFIELD: I don’t know. It’s like you really have something you can work on and you know what you want to work on and you do, You learn that little thing. It actually gets inside you so you can use it as an improviser. Other days, just, you know, whatever, you know?

Q: Yeah, I hear you. Do you have practice books that you use?

SCOFIELD: No. I learn tunes. I get that out of fake books and listening to other people’s recordings of them. And then I transcribe licks a little bit. Not a whole lot, but I’ll hear some cool thing that one of my idols played on a record and I’ll figure it out. Those are in a book that I keep and go back to.

Q: Do you like, take a four-bar lick, or a 16-bar lick or a phrase?

SCOFIELD: No, it’s like two bars. Two bars. Or maybe four bars.

Q: So just a pattern of sorts.

SCOFIELD: Yeah, what is that pattern? What is the relationship between the chord that’s being played on the song? And the rhythm.

Q: Are you of the belief that, especially with jazz standards, that you should learn the lyrics too?

SCOFIELD: There are a lot of standards I know that I don’t really know the lyrics to.

But I notice that when I do know the lyrics, it really helps me to play them. Not because I’m thinking of “Moon in June,” but the syllables teach you the song in a different way than do-re-mi, than just the notes. It’s maybe subconsciously and I don’t know it, but if I do know the lyrics —

(sings)

“There will be many other nights like this

And you’ll be standing there with someone new,”

Which is “There Will Be Another You.”

But when I just knew it as:

(sings)

“Da-da-da-da-doo-da…

Da-da-da-da-da-da-da-doo-da.”

I might kind of fuck it up or do it differently. I don’t know, but It helps me to know the lyrics. There are a lot of tunes that I don’t really know the lyrics to. I kind of know the lyrics. The first line or the second line and then I make up something else. There are some tunes I play wrong.

Q: What tunes are those?

SCOFIELD: I don’t know. But there are some standards that I realize, oh, I don’t really play that the way it was written. But hey, I don’t care, because that’s what happened in jazz. It became music that we share and so much for Irving Berlin. He’ll just have to live with the fact that we’re not playing it the way he wrote it.

Q: And there’s nobody standing over you with a baton rapping you on your head.

SCOFIELD: Irving Berlin doesn’t call me up and tell me.

Q: How do you audition musicians for your groups?

SCOFIELD: I just listen to guys that I like they’re playing and then I ask them to play with me and hopefully they want to. I just... And I talk to other people, other musicians that I respect and they say, “Oh, this kid’s great!” And then I listen to them. I do audition them in that I ask them to come to a jam session. And you see what it feels like.

Q: So you’ll jam with your group and you’ll throw these guys in.

SCOFIELD: Not on a gig, really. More, I’ll get a place to play and invite them to come meet me at the jam.

Q: Do you know it instantly? Instantly is it like, “Oh man, this guy’s got it.”

SCOFIELD: Almost, yeah.

Q: And how important is the personality of the person that you play with?

SCOFIELD: It’s not that important. It’s really weird.

Q: Is that right?

SCOFIELD: If you can make music with somebody, you can actually not get along with them, but you do get along with them, because usually music is the most important thing to them, and it is to you. So we put up with each other’s differences.

Q: And musicians have been known to be quirky in some ways.

SCOFIELD: Yeah, some. And if you really like playing together, that’s a bond that almost transcends personality. And there are other guys that drive you crazy and whatever, but if you can really play together, you put up with a lot.

Q: Jazz people are so proud, but they can be very cutting at the same time.

SCOFIELD: Yeah, there’s a lot of opinionated, especially younger guys, when they’ve learned about the stuff and it means a lot to them, and they’re like, “Ah, this guy sucks,” and “This guy’s great, much better.” Yeah. I mean, it’s pretty weird. And often not necessary, but maybe that’s just part of life. I’m sure it exists outside of jazz.

COMING IN PART II: Miles Davis; two labels from Munich; jazz education and more.

Excellent interview! Looking forward to Part 2.

The pianist Walter Bishop, Jr. was a friend and he told me that he was once practicing and the keyboard looked up at him, like a monster, and after that, he felt that he too was always trying to tame it.